Powder Compaction: Principles, Processes, and Applications

Powder compaction is a critical manufacturing process used to form solid objects from fine particulate materials, known as powders. It is a cornerstone of powder metallurgy (PM) and advanced ceramics manufacturing, enabling the production of complex, high-performance components with controlled porosity and material properties. The process involves applying pressure to a powder mass contained within a die, causing the particles to rearrange, deform, and bond to form a coherent, but typically fragile, "green" compact. This compact is then usually sintered at high temperatures to achieve final strength and density.

Fundamental Principles of Powder Compaction

The science behind powder compaction is based on the behavior of granular materials under applied stress. The process can be conceptually divided into several stages:

1. Particle Rearrangement

Initially, as low pressure is applied, loose powder particles slide past each other, filling voids and achieving a more efficient packing arrangement. This stage results in a rapid initial increase in density.

Figure 1: Initial stage of powder compaction: particle rearrangement and void reduction.

2. Elastic and Plastic Deformation

At higher pressures, particles undergo elastic deformation (reversible) followed by plastic deformation (irreversible). For ductile metal powders, particles are forced into contact areas, creating cold welds or mechanical interlocking. Brittle materials may fragment, creating new, smaller particles that fill interstitial spaces.

3. Work Hardening and Final Densification

Continued pressure leads to work hardening of the particles, increasing resistance to further deformation. The goal is to maximize inter-particle contact area and minimize porosity, though complete elimination of pores is rarely achieved in the compaction stage alone.

Primary Compaction Methods

Several techniques are employed for powder compaction, each suited to different part geometries and production requirements.

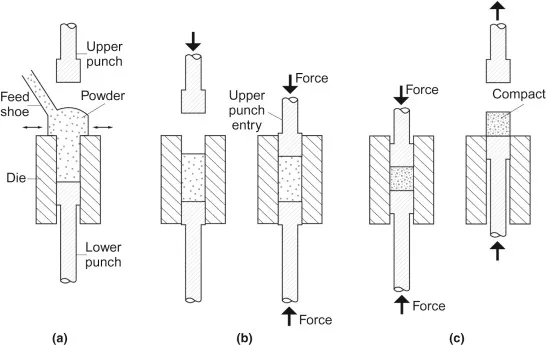

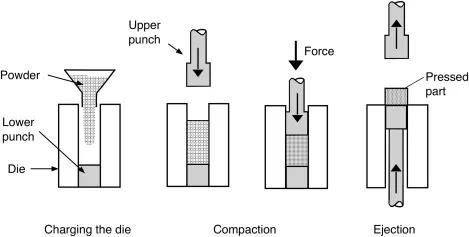

Uniaxial (Single-Action or Double-Action) Die Compaction

The most common method, where powder is filled into a rigid die and compressed between two punches. Double-action pressing, where both upper and lower punches move, provides more uniform density distribution.

Figure 2: Schematic of uniaxial double-action die compaction.

Isostatic Compaction

Pressure is applied uniformly from all directions using a fluid (liquid or gas) within a flexible container. This method yields compacts with exceptional density uniformity and is ideal for complex shapes.

| Parameter | Uniaxial Die Compaction | Isostatic Compaction |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure Medium | Rigid Punches & Die | Fluid (Oil/Water/Gas) |

| Density Uniformity | Moderate (Gradient possible) | Excellent (Isotropic) |

| Tooling Cost | High | Lower (flexible molds) |

| Production Speed | High | Lower |

| Typical Applications | Gears, bushings, simple shapes | Spray nozzle, turbine blades, complex forms |

Powder Injection Molding (PIM)

Powder is mixed with a binder to form a feedstock, which is then injection molded. The binder is later removed, and the part is sintered. This allows for extremely complex, net-shape geometries.

Critical Process Parameters and Their Effects

The quality of the green compact is governed by several key factors:

- Compaction Pressure: Directly influences green density and strength. Too low pressure results in a weak compact; too high can cause lamination cracks or excessive tool wear.

- Powder Characteristics: Particle size distribution, shape, morphology, and hardness significantly affect compressibility and final density.

- Lubrication: Internal (mixed with powder) or die wall lubricants reduce friction between particles and between powder and tooling, improving density distribution and enabling ejection.

- Compaction Speed: Affects the time available for particle rearrangement and air escape. Too fast can trap air, leading to defects.

Figure 3: Typical relationship between applied compaction pressure and resulting green density.

Applications Across Industries

Powder compaction is indispensable in modern manufacturing. Its applications include:

Automotive Industry

Production of high-strength, wear-resistant components like connecting rods, transmission gears, and valve guides with excellent material utilization.

Aerospace and Defense

Manufacture of heat-resistant superalloy turbine blades, tungsten heavy alloy penetrators, and other critical high-performance parts.

Medical and Dental

Fabrication of porous implants for bone ingrowth (using space holders), and dental restorations from bioceramics.

Electronics and Magnetics

Production of ferrite cores, tungsten contacts, and heat sinks with tailored electrical and thermal properties.

Despite its maturity, powder compaction faces challenges such as density gradients in complex parts, limitations on aspect ratios, and the cost of tooling. Future advancements focus on simulation-driven design (using Finite Element Analysis to predict density and stress), the development of novel binder systems for advanced PIM, and the integration of additive manufacturing techniques with traditional compaction to create functionally graded materials and unprecedented geometries. The drive towards sustainable manufacturing also emphasizes the near-net-shape capability of PM, which minimizes material waste and energy consumption compared to subtractive processes.

In conclusion, powder compaction remains a vital and evolving technology. Its ability to transform engineered powders into precise, high-value components ensures its continued centrality in the production of materials for the automotive, aerospace, medical, and industrial sectors, bridging the gap between raw material science and finished engineering products.